You can listen to this (astonishingly accurate) AI summary of this article:

There are shockingly few books in Iranian bookstores. So I took matters into my own hands and made my own books. I would find English-language books and essays online and print and bind them together myself. I gave titles to my bundles of printed texts and even drew cover art for my favorites. They were precious to me and having them was a crime. All writing is presumptively illegal in Iran unless appropriate permits are obtained. To get the permission to read them, I had to petition the Ministry of Guidance to issue me a book permit. Had I been born just a few years earlier than 1999, the Ministry of Guidance would have been able to limit my world to the censored books they wanted me to read. My older cousins were only 7 years older than me, but it was as if we had lived in different ages. They could access illegal Western movies if they called the right number, but there was no dealer they could approach to get an uncensored copy of Darwin’s Origin of Species. Maybe if they, too, had online access to any book they wanted and knew English to read it when they were young, they wouldn’t have grown up to become as brutish as they were. Using these two gifts, I read enthusiastically about everything from the formation of glaciers in Antarctica, to formal logic, to J.S. Bach’s musical composition. It would not be an exaggeration to say that everything I knew, I had learned on the internet. I felt a wistful sadness about the best of my classmates who wanted to learn but whose only source of gaining knowledge was the pathetic textbooks we had. At school, I sat at the very back of the classroom and read my makeshift books. The teachers usually didn’t mind that I was quiet and reading. But Mr. Aghilian, our Religion teacher, was not so tolerant. He was a pudgy Mullah with a dark prayer mark on his forehead and a sardonic smile on his face. I had heard some chatter in the school about him being a regional commander in the Basij (abbreviation of “the Mobilization Force for Resistance,” the paramilitary defending the Islamic revolution). I was reading a book I had made about the greatest construction projects when I felt his presence above my head. He seized my book with a jolt. I looked straight at him.

“Why isn’t your My Religion book open in front of you?”

He looked at the book.

“What is this you’re reading?”

“An essay about the construction of the Golden Gate Bridge.”

The black and white picture of the Golden Gate Bridge was dangling in his hands. “What? This? Heh! What’s good about that? They connected two tin rods and colored them yellow.”

“Yet no one can build anything like that here.”

The smile on his face faded and he put on a pensive look.

“An Islamic society focuses on much more important things than craft projects. We’re here to bring the end of time and create an ideal world.”

Without skipping a beat, he continued:

“And where do you think Westerners learned to build things like that anyway? Everything the Westerners know comes from us. Didn’t you know it was our Islamic thinkers who gave science to them? It is our knowledge that they stole. We can build whatever we want if we want to. We decided to crack the atom and a couple of our brothers did it in Natanz with ease.” he said, while gleefully tearing my book to pieces.

“The only thing Islam taught the world was death and destruction.” I half-whispered in angry rebellion. I didn’t want him to hear, but he did.

“SHUT UP! You are a secret infidel! You deny God! I will show you!” He smacked my face and I tasted blood in my mouth. He threw me out of the class and said, “I will take care of you soon. Just watch me.”

I knew what his threat meant. He was going to report me to the Basij and have me arrested and perhaps killed. When I had come to the school that morning, I did not know that I would receive a death threat from my teacher.

My school principal’s reaction was to blame me. My parents did the same. I told many people that my teacher not only assaulted me but threatened me with death. And no one took my side. They blamed me for speaking and told me that I deserve anything that comes to me.

I now believe anyone whose moral compass is not severely broken would have taken my side. But I could not find any supportive voice around me then. People on the streets witnessed defenseless women being lynched for their hijab and saw nothing wrong with it.

Iran is a relic of the past ages in the 21st century. People on the streets witnessed defenseless women being lynched for their hijab and saw nothing wrong with it. Historically, the default state of human beings is to be Iran; to be indifferent to injustice and unable to tell right from wrong. It is a modern mistake to think that everyone (or every culture) cares about human lives by default. It is a mistake to think that most mothers in every culture care about their children. In the Middle East, the more religious families would happily sacrifice their children for their faith. The idea that their religious code matters less than a person’s life is baffling to most people in Iran. In their eyes, the social dress code is more important than your bodily integrity. In their view, by contradicting Islam or its edicts, I had forfeited my life and couldn’t complain if someone assaults, robs, or hangs me.

I was in a serious situation. I had to get myself out of that somehow. Thankfully, I had learned from similar past situations and had devised a strategy for getting out of them. I had read a couple of Islamic books and had memorized minute facts about Sharia so I could invoke my knowledge as a smokescreen and make others think that I am actually a devout Muslim.

I asked the principal to bring me back to the class so I could apologize. In front of others, I took a deep breath and tapped my memory of those religious books: “Thank you for your care, Mr. Aghilian. Inshallah your strike will atone for my sins in the afterlife.” I took a moment, forcing myself to look solemn. “I find myself very lucky to be living in the only Islamic Ummah of pure twelve-Imami Shia. Whatever its shortcomings, we will be the disciples of Imam of Time when he returns back to earth to bring final victory to devout Muslims. We are the only nation tasked with the awesome responsibility of facilitating his descent from heaven by spreading true Islam as far as we can. I am doing my part by learning about the West so I can be of help in strengthening the Islamic Ummah against them and pave the way with my body and soul for Imam’s triumph.” I said, as if I was on a theater stage.

“No one believed me. Right?” I thought to myself. “How could anyone with a human mind believe these lies?” But the next moment, the entire class started clapping anxiously. The students acted pleased for the teacher, and the teacher smiled for the students. “Please forgive him, Mr. Aghilian. I have no doubt he is a dutiful Shiite child. And he promises to not read anything but textbooks in school from now on.” the principal said. And that way, I managed to dodge a bullet.

I don’t know why they acted convinced. My disdain for Islam wasn’t a secret to anyone. I had talked privately to many of my classmates about the lies and contradictions in what we were taught. No, it’s not true that Iran’s economy is one of the fastest growing in the world. No, Ayatollah Khomeini wasn’t a hero, he killed a million people. No, nothing bad will happen to you if you listen to American music. No, it’s not true that NASA proved that the moon was split in half by Mohammed. No, Einstein never attributed the theory of relativity to the Quran. When I was in middle school, some people seemed to agree with me. But every subsequent year in high school, my arguments seemed to move fewer and fewer people. As people got older, they simply didn’t think about whether something is true or not anymore.

And because of that, I felt extremely lonely.

I understood that not everyone would be interested in ideas. But I thought some things must be universal. How could everyone affirm that part of the Quran that demands the murder of non-believers? Everyone affirmed that they would murder those who decide to quit Islam. I had quit Islam. Was I safe? “Okay,” I thought, “some people are blinded by prejudice. But no matter what they think, music is the universal language. You can’t help but to react positively to Adele’s voice when you hear it.” But when I showed Adele’s music to people, their reaction was repulsion and anger because a woman was singing. It was as if the Islamic state had hollowed out everyone’s souls. I just wanted to see someone who had a soul. I wanted to meet someone who cared. How could others see what life abroad is like and not want it with every fiber of their being? Did they at all see the same wonders in the world that I saw?

My knowledge of the world, my vision of what I wanted out of my life, my strong sense of justice, everything that was good about me (and has today made me fit in the American society) made me painfully stand out from others in an isolated religious totalitarian state like Iran. I felt the same way you would feel if you were teleported into 15th century Europe. I could not find a single person with whom I could relate. And that was a source of constant self-doubt and other-doubt for me. Either I was being unreasonable for wanting a better life, or humanity was rotten for not understanding it and hating me for it.

I would have been isolated forever if not for an app called “Instagram.” It was 2014 and it was relatively new. I realized that artists posted pictures of themselves there. So I searched for one of the artists I liked. Her name was “Marina.” In the results page, something caught my eyes in suspense: “Marina Iran.” That read to me like “The square circle.” I never expected to see those names together. Iran, the Muslim country that hated women and music, and Marina, an unapologetic powerful female singer. I clicked it and saw that there was another person in Iran who liked her as much as I did and was posting about her. Seeing that was like finding alien life. I didn’t know who the person behind the page was. I looked up the latest news on Marina and direct messaged them to the admin to post. Over time, the admin trusted me enough to send a link to a secret fan group chat she had made. In that group chat, I found my best and true friends. I found young intelligent people all over Iran who shared my values.

I met Ayda, a brave girl who despite the tyrannical parents and the extreme domestic violence she was suffering from, wanted to become a writer and had a bookshelf full of classic English fantasy novels.

I met Rana, who had fought her way from her small southern town to Tehran so she could find better job opportunities while in school and save enough money to become a fashion designer in Paris.

I met Sara, a strong girl with the upright gait of a model whose insane level of knowledge humbled me. She had learned everything through the internet as well.

I met Sajad, whose eyes were full of life. He had somehow obtained an electric guitar and had taught himself to play it. His goal was to make it to California and start a band.

I met Sahra, who became the symbol of strength and resilience in my mind. She was a trans girl in a small backward city in Iran who had fought impossible obstacles to exist in an intolerant country like Iran. She had taught herself programming to become independent from her family who wanted to kill her. She, too, was saving to escape Iran.

“These people are me,” I felt. My life became so much richer with them in it. And I found them all through an anonymous Instagram page. Every friend I had in my life, I was able to find because of social media. Either directly, or indirectly.

In a country where society watched gay people thrown off buildings, my friend group was supportive of my sexuality.

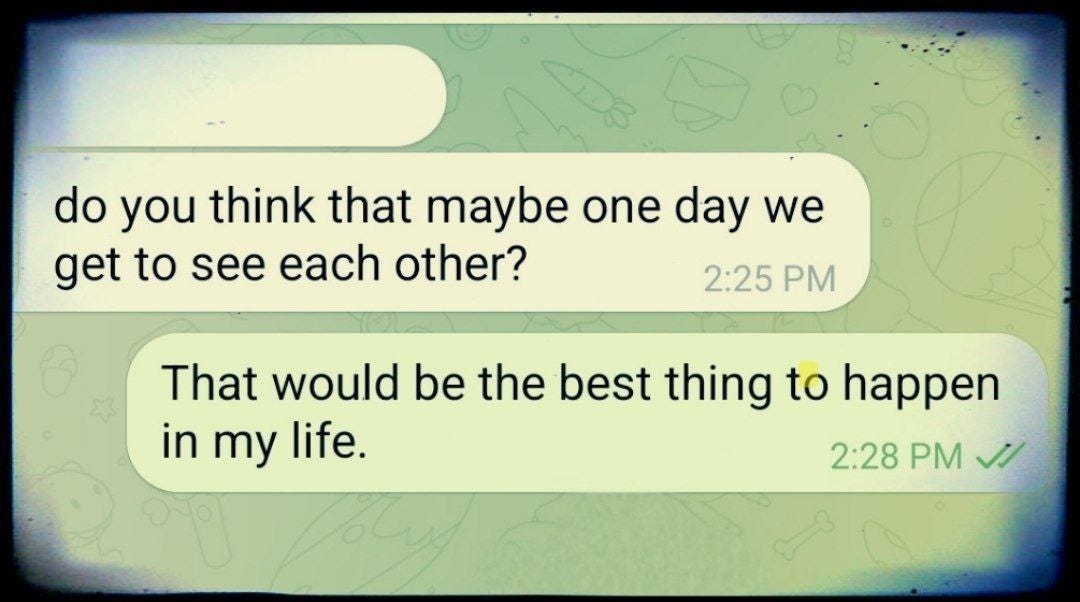

We all had incredible and tragic life stories. We were all victims of a totalitarian dictatorship. We lacked basic freedoms. Our future was grim. But we had each other. We encouraged each other to go on and to work for a better future. We promised each other to escape Iran and meet under the Brooklyn Bridge one day. It was because of them that I was able to hold onto my values long enough to escape. They cried with me through my tragedies and cheered for me to keep fighting my way to America. I owe them so much, and the fact that I am the only one who successfully escaped Iran is the biggest source of sadness and grief in my life.

Because we didn’t have freedom of speech in Iran, we couldn’t have possibly found each other in the real world. We couldn’t let anyone know that we were compassionate people who didn’t believe in the orthodox radical Islamic ideology. We couldn’t show ourselves to others who also loved this world and didn’t want to see it blown up. We didn’t have any power in Iran. Our voices were taken out of our very throats by tyrants. But social media made speech possible for us.

I think we should take into account the positives when we talk about the social media. All I have heard from Americans is how bad and harmful and evil the social media companies are. I’m here to say that those companies saved my life on more than one occasion. My message is really simple: thank goodness for social media. It gave voice to us the voiceless. It empowered some of the least fortunate people on this Earth to find and help each other. It showed me that good people exist. Even in a soul-corrupting hell like Iran.

There are many studies about the negative effect of social media on people. But I don’t know of any papers that studied just how many intelligent lonely people were able to find their desperately needed human connection on social media. That could be the difference between a misanthrope and someone who is in touch with humanity and his values. If we are going to discuss the dangers of social media, we owe it to ourselves and others to also discuss the benefits to those who will find the love of their lives because of a connection they made to someone on Instagram.

The same day that I was assaulted, at the end of the school day, in the empty school bathroom, one of my classmates named Rezvan approached me. He had a slim figure and a very tragic face. He looked around to make sure no one was listening. Then he told me: “I agree with what you whispered there, Nikmand. Aghilian is a scum.” He let a moment pass, then the expression on his face changed: “They are all scum. Everything is bullshit. They just lie to us. We are all doomed. So fuck it all, Nikmand. Enjoy this bullshit life you have before it all ends.” He walked away. Some months later, he quit school and became an addict. I didn’t hear from him again. I can only speculate, but I think if he had found friends who he was able to connect to, he wouldn’t have become so pessimistic about life. That could have been me if I hadn’t found my wonderful friends.

Thanks for that sad and wonderful story of "life" in Iran

Your courage and hope in these texts are truly inspiring! I’m glad you found a way to connect with real friends and like minded people even in the darkest moments. Keep going! 🌱💪

And finally, let me say this, you’re a role model for me and so many others.