This Movie is Why I'm Alive

How Ratatouille showed me the beauty of the world that wished to kill me

On that summer day in 2008 when my mother took me to a bazaar, I didn’t know that I would come back home with the most prized possession of my life.

I was 9 years old. My mom was in a black baggy coverall, similar to a nun’s habit cinched, tightly around her face, leaving only her hands and face exposed. We both bore bruises on our bodies from my father. The weather was 110 degrees, and neither our car nor the bazaar had air conditioning. But my mom took another large black cloth (chador) and wrapped it around her already fully covered body. “I can’t go out without chador! People will look!” was her reason. The bazaar was a crowded corridor with indistinguishable black figures shuffling around. I couldn’t tell my mom apart from them. Most of those figures were meekly asking the shopkeepers whether discounts or scraps were available. And most of those shopkeepers were sitting on a stool munching sunflower seeds. The air was filled with flies and smelled like spice, sweat, and rotten fruits. Foreign goods being sanctioned off from Iran, there were shops selling repaired old appliances at the price of a new one. My grandfather, who recently went to Saudi Arabia, had smuggled a brand-new TV for us. I was excited to watch something on our new TV. “Perhaps I could borrow a CD from my cousin,” I thought. Then I saw a sign on a corner between shops: “Chef Rat cartoon arrived.” “Can you please ask the price?” I meekly asked my mom. “Why are you, little devil, always wasting my time?” she said. “Sorry, sir, how much is the… What cartoon?… Chef Rat.” It was around 20 cents. She walked away. I stayed. After a long, teary protest, I convinced her. “Mother…, I promise, I will eat less so you get the money back. It wouldn’t cost you anything if you don’t have to buy food for me.” She relented.

The suspicious-looking dealer looked around and discreetly produced two unmarked CDs from his suitcase and wrote: Chef Rat.

I borrowed a CD-ROM from my grandmother, and with infinite excitement of confronting the unknown, I watched Ratatouille.

To this day, I get teary when I watch this movie. Those CDs changed my destiny. I was born into a poor, ultra-religious family in the slums of north Esfahan, in Iran, one of the bleakest places in the world. I was so inspired by the movie that I fled Iran the moment I turned 18. My parents had disowned me. I was penniless and completely alone. I was trafficked and held captive as a slave for 5 years. I had to face unbearable pain, hopelessness, and horrors. But what inspired me to flee, also stopped me from giving up; the bootlegged movie on those CDs: Ratatouille (2007). It was not the only foreign movie I had watched, but it felt very different from everything else I watched later. I watched Ratatouille almost every week in Iran. And the moral lessons I got from it made my life infinitely better and turned me into the person I am today.

It may surprise you that I am saying that about a commonly watched movie. But I don’t say it easily. Why did it have such impact on my soul at such a young age? What happened to me afterwards? I will explain them together.

The block quotes are from the official Ratatouille screenplay. Source: here.

Ratatouille is about a person named Remy who is a rat born into a dirty, poor, and thieving colony.

REMY:

“This is me. I think it’s apparent I need to rethink my life a little bit. What’s my problem? First of all,”-

OUTSIDE THE FARMHOUSE - DUSK - WEEKS EARLIER A SILHOUETTE darts out from behind a wooden barrel, pausing upright against a blood red sky. Mangy, sinister, the opposite of Remy. This is how most humans see RATS.

REMY (CONT'D):

-“I’m a rat. Which means life is hard.”

The colony lives uninvited in a farmhouse and scavenges food scraps for survival. Unlike others, Remy has poise, cares about things, and wants to eat delicious food. He also stands out from others by how clean he is. He walks straight on two paws where others don’t.

As a child, I just fell in love with Remy and wanted to emulate him. He was the only role model I had. At school, I didn’t let my belongings and uniform get dirty and I walked with self-conscious poise. I did not sit on dirty ground like everyone else. I was laughed at. I was even punished by the school for not following others when they sit on the ground.

Remy learns that human beings, his enemies whom he shouldn’t admire, live a much more advanced and enjoyable kind of life than they do.

Remy watches the farmhouse, drawn to the warm light and the sounds emanating from inside.

REMY:

“I know I’m supposed to hate humans. But there’s something about them...”

FARMHOUSE - KITCHEN Remy carefully sneaks into the kitchen.

“...they don’t just survive, they discover, they create. Just look at what they do with food!”

Enchanted with man-made food, he daringly learns how to read and cook, familiarizing himself with different flavors and techniques among the few resources he has. His family disapproves of his ambition, but he does not back down.

EMILE:

“Wait-- you.... read?”

REMY:

“Well, not... excessively.”

EMILE:

“Oh, man. Does dad know?”

REMY:

“You could fill a book-- a LOT of books-- with things dad doesn’t know. And they have. Which is why I read.”

Remy loved books, and that inspired me to read. At the age of 10, I read every book I could understand on every bookshelf I could find. I kept the habit of reading. My favorite genre was science, and soon, I had read every science book published in Farsi.

Remy’s favorite chef and mentor is Gusteau, whose motto is “everyone can cook.”

GUSTEAU (TV):

“You must not let anyone define your limits because of where you come from. Your only limit is your soul. What I say is true, anyone can cook... but only the fearless can be great.” Remy grins, nodding in agreement.

REMY:

“Pure poetry.”

I froze the frame here. Gusteau’s book was in English. I wanted to learn how to read it. My parents strongly objected, but I fought with them until they backed down and allowed me to study English.

The owner of the farmhouse suddenly discovers the colony, forcing the rats to evacuate. But Gusteau is so important to Remy that he risks his life to take the Gusteau’s cookbook with him.

DJANGO:

“EVACUATE!!! EVERYONE TO THE BOATS!”

RATS grab assorted belongings as they make their escape. Remy and Emile run with the terrified mob. Suddenly, Remy stops, looks back to Gusteau’s COOKBOOK-

REMY:

“The book!”

--and TURNS BACK, rushing into the flood of fleeing rats!

Remy, the last remaining rat, struggles with GUSTEAU’S COOKBOOK. A strange BREATHING SOUND causes him to look up: the LADY is back, now sporting a World War 2 GASMASK, and GAS CANNISTER. She starts after Remy, SPRAYING GAS everywhere.

He struggles to catch up with his colony and loses them. He is washed down with rainwater down the sewer.

After seeing that horror and losing his colony, he is dejected and understandably feels that he lives in a hostile world. But his image of Gusteau urges him to go up and explore the world above. He does. And climbing up, instead of finding a depressing world, he finds himself in Paris. A city where so much is possible.

OUTSIDE THE BUILDING - ROOFTOPS - DUSK CAMERA follows as Remy scampers along railings and ledges, past windows, up vines, BOOMING UP as the ROOFTOP FALLS AWAY TO REVEAL- A STUNNING PANORAMA; PARIS AT NIGHT. It is GORGEOUS-- a vast, luminous jewel. Remy is GOBSMACKED. REMY:

“Paris? All this time I’ve been underneath PARIS? … It’s beautiful!”

We see what makes Paris so great for Remy: Gusteau’s restaurant.

Remy’s takes in the sea of shimmering lights... then sees a HUGE SIGN atop a building several blocks away. It’s GUSTEAU-- a frying pan in each hand. The SIGN marvels at the panorama.

GUSTEAU SIGN:

“[Paris is not just beautiful, it’s] The MOST beautiful.”

This scene has been, more than any other image, as alive as a shining star in my mind since childhood. When I first watched the movie at the age of 9, the main thing I learned was that there is a place called Paris that is more incredibly awesome than anything I could have imagined. This scene was the first esthetic experience of my life. It taught me to appreciate beauty. Over the years, it became the emblem of what I wanted to reach in my life. Growing up in a menacing dictatorship, I regularly witnessed pure ugliness; from my father’s animal rage to the senseless brutality of corpses hung in public, to people’s evasive eyes and broken posture under crushing living conditions, to news of my friend’s suicide. It all would have consumed me if this movie hadn’t shown me that Paris was within reach. “It’s okay. I’m in the sewer right now. If I climb up, I will reach Paris,” I told myself. And even though I had heard that going to Paris is impossible for someone with an Iranian passport, the warmth of Remy reaching that Paris panorama gave me the assurance that I can make it, and life is worth it. If Remy got to Paris and made a glorious life for himself as a rat, how hard can it be for me as a human to do the same?

Remy arrives at the restaurant of his hero, and watches it from above, basking in excitement. But he accidentally falls into the kitchen, and instead of escaping he prefers to risk his life to fix a badly made soup.

[During his escape,] His gaze returns to the boiling pot. He looks back at the kitchen: the cooks haven’t noticed him. He looks at the window: it is still open, and the path to it is clear.

GUSTEAU:

“Remy! What are you waiting for? You know how to fix it. This is your chance...” Remy considers this. Then, filled with purpose, he jumps to the stove top, turns the burner down, hops up to the spigot to add water to the soup. Quickly losing himself, Remy proceeds to remake the soup, alternately smelling, tasting and adding ingredients to it.

Remy inspired me to be brave. Between the feeling “I’m a rat, I should know my place,” and “I can fix this soup,” he chooses the latter. He could have been caught if seen in that kitchen. But instead of stress and anxiety, he is alive, fearless, and filled with purpose. The music in the background stresses that with a playful arrangement, blending orchestral elements that evoke a sense of adventure and purpose.

He is caught and almost killed for going into that kitchen. But he finds an unlikely friend there. Linguini, the garbage-boy who saw him make the soup recognizes Remy’s intelligence and befriends him. They go back to Gusteau’s kitchen and Linguini starts cooking. Unbeknownst to everyone, Linguini is just following Remy’s movements. Remy’s wildest dream have come true; He is cooking in Gusteau’s restaurant!

Working in Gusteau’s kitchen, Remy learns that cooking is not as easy of a task as he thought. He feels intimidated by the other chef’s demands for excellence, but happily puts his best effort into learning and eventually masters the skills he lacked.

One night, a patron of Gusteau’s is tired of old dishes and asks for a new dish from Linguini. The head chef, Skinner, sets them up for failure by asking Linguini to make an old, failed recipe. Remy decides that the recipe needs changing, so he improvises to re-make the dish according to his own standard, despite what everyone wants.

COLETTE (she looks in his pan):

“You are improvising?? This is no time to experiment, the customers are waiting!”

Remy’s risk pays off and his dish becomes a huge sensation and is re-ordered many times.

Remy slaps his paws together, relishing the night ahead.

MONTAGE Crosscut between the dining room and the kitchen: orders pile up as word of the “special” spreads between diners. Remy pilots Linguini, preparing plate after plate of their hit.

The music of that scene has a lively and intricate orchestration, conveying a sense of urgency and precision, and reflecting the high stakes and meticulous nature of preparing a special order in a top-tier restaurant. The happiness on Remy’s face when he gets more orders, accepting the fulfilling challenge of a long light’s work shattered my perception toward work.

Reflecting the world around me, I thought work was drudgery. I was surprised by what I felt watching this movie. It was showing just a normal workday. He only made a dish; he didn’t save the world or jump into a fiery building. So why did it feel like that? Remy’s success felt so triumphant. It made me feel as if his work was the most important thing in the world. This caused a big shift in my view of what a good life looks like. The image of glory in my mind was not a soldier jumping on a grenade for Islam any longer, but Remy making a new dish. Perhaps the society I lived in was wrong about greatness. Perhaps, in Remy’s words, what is great in us is that “[we] don’t just survive, [we] discover, [we] create. Just look at what [we can] do with food!”

At 12, I realized that there is a huge difference between Iran and the West. I could understand English well by that age. Through English books, I learned about the world. I listened to my first American music through internet. I learned about skyscrapers. I learned that in “abroad,” when they are full, they just stop eating and leave food behind! The rest of the world thinks of Paris, New York, Houston, Berlin, Honolulu, and Tokyo as very different places. But to me, looking from the miserable backwardness of Iran, they are all the wonderful, shining, unattainable, “abroad.” I realized that Remy could’ve been in any of these cities. The difference was real to me now. Whose life was I living in Iran? The difference between the poverty and grimness of Iran and the clean excitement of abroad reminded me of the difference between the humans and rat colonies in Ratatouille. I suddenly realized that I was in the same situation as Remy; stuck in a rat-like Islamic colony. I decided that someday, I will follow his footsteps and make my way to my Paris. But it was all a vague abstract desire. I didn’t know what to do if I made it abroad. I didn’t care about cooking that much.

At 14, I understood who Remy really was. What was cool about Remy’s life was that he was bringing new things to the world. He was an inventor!

I went on a mission to figure out who invented the things around me. I read more about science and technology. Specifically, I was enchanted with the smartphone revolution. The first time I held an iPhone in my hand, I was infinitely charmed by touchscreen technology. How could it know what is just an object and what is my finger?! I had to learn. I read the labels on everything to find out where they were made. And without exception, every single thing I found was invented abroad. Where were iPhones made? San Fransisco. Where did cars come from? Tokyo. What about penicillin? London. There were many people in the world living like Remy, adding all these creations to the world. I still remember the dizzying excitement I felt: the promise of Ratatouille was true! I could for real be an inventor like Remy if I leave Iran. That was the easiest decision of my life.

After that successful night, Remy lies down, spreading his body and enjoying the food he earned. Earlier in the movie, we see him refuse to steal food because he is a cook. Now he is earning his food and would never have to steal again.

He finds his lost family in Paris and goes to visit them. His father, thinking he is forever reunited with the colony, is startled to learn that Remy is working in a kitchen and wants to show him what a mistake he is making.

DJANGO:

“You’re not staying?”REMY:

“It’s not a big deal, Dad. (gently) You didn’t think I was going to stay forever, did you? Eventually a bird’s gotta leave the nest.”DJANGO:

“We’re not birds, we’re rats. We don’t leave nests, we make them bigger.”REMY:

“Maybe I’m a different kind of rat.”DJANGO:

“Maybe you’re not a rat at all.”REMY:

“Maybe that’s a good thing.”

“Rats! All we do is take, Dad. I’m tired of taking. I want to make things! I want to add something to this world.”DJANGO:

“You’re talking like a human.”REMY:

“Who are not as bad as you say.”DJANGO:

“Oh yeah? What makes you so sure?”Remy hesitates for a beat, suddenly careful.

REMY:

“I’ve uh, been able to, uh, observe them at a close-ish sort of range.”DJANGO:

“Yeah? How close?”REMY:

“Close enough. And they’re, y’know, not so bad. As you say. They are.”Django GLARES at Remy, scrutinizing him.

DJANGO:

“Come with me... I got something I want you to see.”PARIS STREET - NIGHT It’s raining harder now. Django and Remy arrive at a drain opening, through which can be glimpsed the rough cobblestones of a city street.

Django scrambles out the curb-side drain and turns to face the storefront behind them. Remy sits next to him and looks up, following his father’s gaze. His jaw drops in horror.

Displayed in the window of the small shop are a variety of nasty looking metal traps, RAT TRAPS to be precise, and alongside of those hang row after row of DEAD RATS.

DJANGO:

“Take a good, long look, Remy. This is what happens when a rat gets a little too comfortable around humans.”Remy looks away. Django’s tone is tender, but firm.

DJANGO:

“The world we live in belongs to the enemy. We must live carefully. We look out for our own kind, Remy. When all is said and done, we’re all we’ve got.”His point made, Django turns to go. Remy stares up at the horrible window, then softly says- “No.”

DJANGO (stops in his tracks):

“What…?”REMY:

“No, Dad. I don’t believe it. You’re telling me that the future is-- can ONLY be-- (points at window) --more of this?”DJANGO:

“This... is the way things are. You can’t change nature.”REMY:

“Change IS nature, Dad. The part that we can influence. And it starts when we decide.”With that, Remy turns and-- walking upright on two legs-- starts back to Gusteau’s. Django calls after him.

DJANGO:

“Where you goin’?”REMY:

“With luck... forward.”

Even after all these years, the magnificence of this scene leaves me in awe. Remy is violently confronted with the fate of those who dared to get close to humans, knowing full well that he also could die taking the risks of being a chef. He goes on taking the risk because he thinks the relationship between rats and humans doesn’t have to be that way, and if he can find humans who see the good in him, the risk is worth it.

This scene taught me to be brave. Most people in Iran struggle not to admit just how horrible life is in Iran compared to normal countries. I was laughed at when I said I wanted to be like Remy and move abroad.

“What for?” they asked me. “Why think about what you can’t reach and make life harder for yourself? Accept that you are living in an Islamic dictatorship. Read the Quran instead of learning English. Accept the supreme leader’s wisdom. You said Paris? You think the Whites will just let you leave Iran and re-settle in their city?!”

I did not listen to them. They sounded like Django. And I wanted to be Remy. It did not matter that I was alone. I would be the first one in my family who makes it abroad. At 16, I understood why they laughed at me: the world is such that getting a visa and escaping Iran without having an inconceivable amount of money is impossible. I was being the unreasonable one for wanting to escape Iran. Getting a visa was really as hard as they said. Seeing the impossibility of my childhood dream, I thought of giving up and committing suicide many times. But something within me was pushing me to be brave and not give up without trying. It was the sound of Remy as a distant memory.

Most people in Iran at some point realize that every country stops them from entering because they have an Iranian passport, and their reaction is envy of the West, hopelessness, hatred of themselves, of Iran, and of the world. So many of my peers who loved the West as much as I did, gave up on their lives in desperate wistfulness of wanting to reach the unattainable. Convinced that there was no way, the best of my friends fell like fallen soldiers who decided to die with their flag of hope rather than live as a captive. Sara gave up. Ayda gave up. Salar gave up. I was the only one went on and got out. I don’t think I could have persevered if I hadn’t watched Remy refuse to give up.

Anton Ego is a fierce and respected food critic who is disillusioned by cooks in Paris because he thinks there is no more originality in the field of cooking. Looking at Gusteau’s new fame with suspicion, Ego makes a reservation at Gusteau’s to evaluate their food.

The injustice of Remy getting no credit for the restaurant’s success, breaks the friendship between Remy and Linguini. Meanwhile, Chef Skinner who realizes that Remy is the mind behind Linguini’s success, traps and enslaves him, forcing Remy to make new recipes for him in exchange for Skinner not killing him.

A HINGE DROPS, trapping Remy inside a CAGE. A SHADOW looms over them. SKINNER picks up the cage, grinning ear to ear.

SKINNER

“You may think you are a chef, but you are still... only a rat.”

The entire world was saying the same to me. “You may want to be an inventor, but you are still… only an Iranian.”

Being enslaved again because of his rat-ness, he begins to doubt whether he should want cooking at all because that is what only humans do. Then the knowledge hits him: who cares whether he is a human or a rat? He is a chef! And that is what really matters.

Remy is freed and sprints back to Gusteau’s to cook for Ego. He does not care that he is not accepted there. He cooks proudly and openly, without Linguini, and delivers his best to Ego. Ego is “rocked to [his] core” by the dish and demands to see the chef. He learns of Remy and crowns him the best chef in Paris. Having reached his dream, Remy sits in front of Eiffel tower, enjoying his newly earned pride and tranquility. He opens his own popular restaurant with those who believe his ability to cook is what defines him, not his rat-ness.

THE END.

What happened to me? Following a great struggle, I made it abroad, where I am now.

What do I think of the Western world now that I’ve seen it?

After I finally left Iran, I thought nothing is going to stop me. But in fact, I was faced with even greater prejudices and obstacles. I made it into a rich country to chase my dreams, but I was starving to death because I had no money and legally they did not allow me to work to earn money. At 18, filled with so much energy to live, I was so poor that a common cold almost killed me. A cruel predator trafficked me to a different country and held me as his slave, kept me in his house like an animal, and raped me for years. The doors were open, but I could not escape. Why? Because someone who doesn’t have the right immigration papers is not allowed to live outside.

I learned that the West is one unbearable contradiction.

There were so many opportunities to create, so why was I starving to death? I had no money, so why didn’t they let me just work? There were hospitals that could treat me, so why did I almost die from a common cold? There were so many rooms for rent, so why didn’t landlords want to rent to me after seeing my darker skin? I loved technology and had read hundreds of books since childhood, so why couldn’t I just study at a university without a visa? People on the streets lived in unimaginable freedom, so why couldn’t I be free also?

Twelve years after watching Ratatouille, in 2021, I visited Paris, France. My childhood dream came true. But the 9 year-old me had not understood the price I would have to pay to see Paris. I was taken there as a captive, without my choice. After basking in its beauty, at midnight in the hotel, I was quietly crying in the bathroom, feeling the fresh violent pain of rape on my body. Paris was beautiful, the Remy life did exist in the world, but I was locked out of it by an inexplicable injustice. I noticed that the same evils that I faced in Iran are rampant in the West.

So many times I thought of giving up, giving a salute to the world I loved but could not reach, and end my life. But the image of Remy overcoming everything kept me going like the light of a distant star.

It is true. There are many people in the West who would rather see me die in Iran than let me live. They are responsible for making this nightmare world where it is hopelessly impossible for majority of people in it to have a good creative life if they are born into the wrong family. Reaching a good life should never be so difficult for anyone.

But the West is also full of inspiring people whose creative work made these countries so amazing and free. It is full of people who made it possible for a 9-year-old slum kid in Iran to conceive of a good life. I am thankful to them. To Jan Pinkava, Brad Bird, and Jim Capobianco for writing Ratatouille, to Michael Giacchino for composing the enchanting score that made the movie emotional, to the tens of people in the art department who made the story visual, to the founders who made it possible, and to the hundreds of investors who paid them.

I am thankful to those who understood the nature of my journey and helped me get to America. I am standing on the shoulders of thousands of incredible people whose creative work made the life I live today possible. To be sitting in a coffee shop in Austin, Texas, writing this and recovering from my painful journey instead of being executed in Iran for speaking, or simply for being gay, is a miracle. At age 25, I am finally free to build my dream.

But tell me, dear Western reader, why did it have to be so painful? Why is there so much injustice in this world?

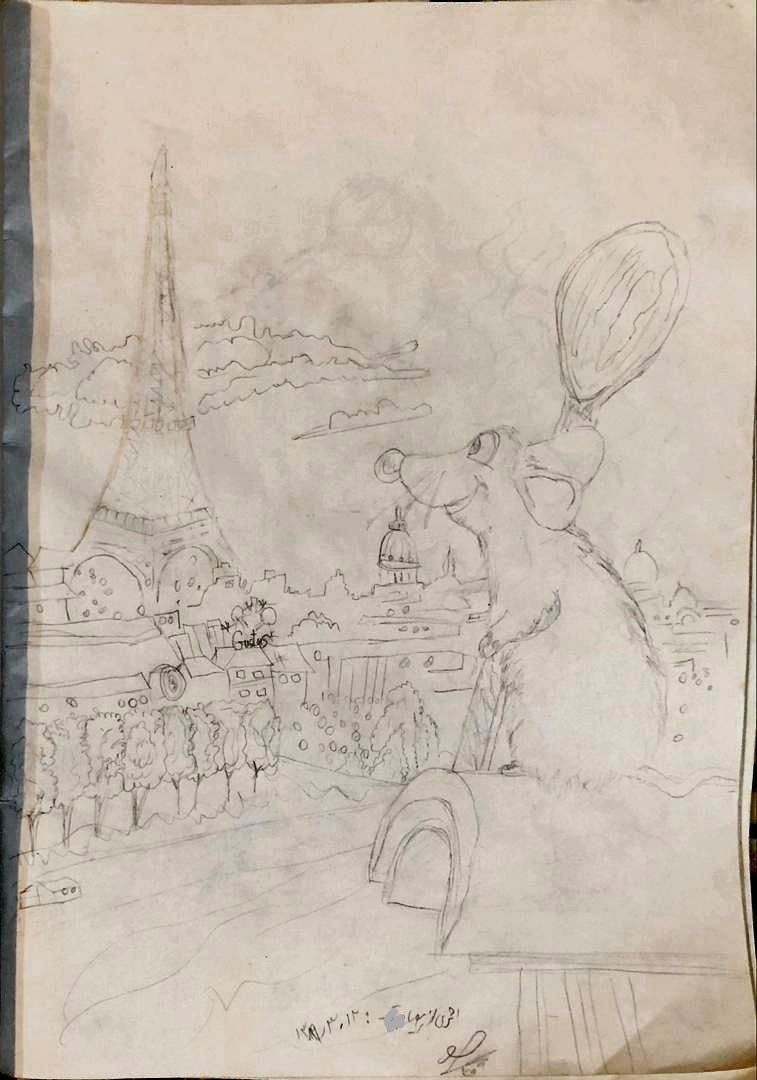

(Image: My drawing of Ratatouille dated 06/02/2010 (11 years old))

When I was spending a few teary hours writing this article I could not have imagined that it would be received so positively by so many amazing people. I was shy about telling my life’s journey, and now I am committed to writing more. If you would like to read more of what life is like for ambitious people born in the Iranian dictatorship, please subscribe.

What a shining concretization of the inspirational power of art! Your heroic journey is also an inspiration. Thank you.

This is an excellent proof of the power of Art. Also that we can find that power anywhere. Good luck out there.